The limited State of Emergency (SOE) and Zones of Special Operations (ZOSOs) have shown positive impact on containing the country’s murder rate and serious crimes. Reports from the JCF indicate that 300 less lives have been lost up to November 2018 than for same period in 2017. The government has decided to extend the SOE and ZOSOs to January 31, 2019. Prime Minister, The Right Honourable Andrew Holness has announced that the government will be establishing 20 more Zones of Special Operation. Those measures require corresponding efforts in building a culture of lawfulness in order to achieve sustainable crime reduction and improved public security.

A culture of lawfulness involves changing the norms of lawlessness and building citizens’ aversion to crime, violence and offending. This is attainable by building capacity within the police force and the criminal justice system; swiftly and decisively dealing with all criminal matters; clearing case backlogs and expanding the role of the police officers to proactively prevent violent crimes rather than being deliberately reactive as they are now.

If a culture of lawfulness is to be entrenched in the Jamaican society we should ensure that those who are employed by the government to uphold the law and to assure public safety and security are accessible to the general population. This is possible through strategic location of police stations in proximity to communities. Where communities consist of 400 or more homes there should be community police stations as part of basic services. Proximity Policing means that the police are accessible to citizens without the challenges of lack of transportation, distance by road or any other factor that may place the police out of citizens’ reach when they are most needed.

The generous distribution of police stations to increase access and achieve security through proximity policing is important, however, this should be coupled with the co-location of Courts. This should be done to ensure that every citizen in Jamaica has easy access to the Courts. In addition, when matters have to be heard by the Court, citizens’ attendance should not be impeded by lack of transportation, distance or serious loss of time from employment or other activities. On the contrary, when the Courts are placed outside of the reach of the citizens they may lose interest in cases and the criminal justice process. This can result in some citizens resorting to community self-help, that is, turning to violence to solve ordinary disputes or engaging in jungle justice.

It is extremely important for Jamaica to build a culture of lawfulness so that the average citizen may regularly experience the dispensation of justice by way of due process in his/her community. In fact, citizens should be able to attend court cases, listen to arguments on either side, whether prosecutors and defendants or litigants and defendants. This kind of interest in justice should be encouraged so that citizens have a comprehensive knowledge and understanding of the process of how conflicts, disputes or breaches of the law are heard and treated within the Courts. In the event that a citizen should appear before the Court he/she would have prior knowledge of due process, fairness, credibility and competence of witness which will assist him/her in embracing the law and shunning any suggestion or temptation to resort to violence or jungle justice. Moreover, the proposal of re-establishing Courts in proximity to local police stations should be embraced due to the fact that this will reduce travel time for police officers and address the problem of their absence from the communities they serve because of court attendance.

Amending the Jamaica Constabulary Force (JCF) Act to enable the police to intervene in civil matters is another effective mechanism to build a culture of lawfulness. The JCF Act defines the police duties as the preservation of peace and good order, protection of life and property, prevention and detection of crime. The Act explicitly excludes the police from taking an active role in the execution of civil process. It prevents the police from being proactive in assisting in the resolution of non-criminal disputes in communities. Very often these non-criminal disputes fester and become grievous matters which morph into situations where violence against people, property or generational conflicts ensue in some communities. The limitation of the law therefore functions as a shackle to police officers and curtails their response and effectiveness. Often times, their only option is to advise the complainant to file civil proceedings through the Court rather than taking proactive action. This deficit is counter intuitive to proactive policing. It would be much better for the police to be trained to appreciate and assist citizens in filing small claims or actions on their behalf. Citizens in the lower economic bracket of the society would therefore be able to have civil matters addressed through the services of the local police officers who would have received training and are subsequently empowered by the law to file civil actions and make submission to the Courts at no cost to the citizen. Consequently, commercial disputes, neighbour on neighbour disputes, and domestic disputes which do not cross the criminal threshold but have the potential to generate violence could be intercepted and placed before the Civil Courts at an early stage.

In the mid 1990’s, the government embarked on a programme of rationalization of Resident Magistrate Criminal Courts. In doing so many of the small district courts which were co-located with larger police stations were closed down. This has removed access to justice from rural communities and centralized the process in town centres or parish capitals. The problem of transportation and urban violence has resulted in many citizens in the rural communities abandoning the justice system. The proposal for District Courts to be re-established in the rural communities will address the need of ordinary folks having their legal needs attended to, as this will facilitate the handling of both criminal and civil matters. This measure could build back respect, confidence and trust in the justice system as the preferred way of resolving conflicts and dealing with offenders instead of a recourse of community self help and violence.

The positions put forward above are crucial, however, employing the rule of mediation where appropriate to resolve small claims, civil and minor criminal matters should also be explored. The issue of case backlogs in the courts is a perennial sore point in the Justice System. A possible remedy to this situation is the implementation of mediation for less serious criminal and civil matters. Cases which are not of a very serious nature and where there is no serious risk to individuals and the community but which present the opportunity for citizens in conflict to be brought before an objective and independent mediator should be so referred. In mediation, both the victim and the perpetrator are given the opportunity to openly engage in dialogue in order to arrive at an amicable solution. This results in both parties leaving the mediation process satisfied and without animosity towards each other.

Mediation should not be done in a vacuum, it can also be done at the community level by having Judges attend regular community meetings, engaging citizens in discussions and explaining the criminal justice process, the concept of rule of law and why it is important for every civilized society to promote and build rule-based order. There are no better persons to engage and bring value to this kind of discussion at community level than the Judges themselves or the Officers of the Courts. Customarily, citizens’ concerns highlighted in community meetings are addressed by the police but very seldom do citizens hear from Judges unless they are before the courts. This should strongly be considered as a method to correct lawlessness in the society, as ignorance of the law is not an excuse. Ignorance of the law can also be corrected through the launch of major educational campaigns which link the rule of law with improved citizen security, delivery of justice, trust-building, citizens’ confidence and national prosperity.

Mediation, public education campaigns and the active participation of Judges at the community level are preventative strategies which should be promoted as counter measures to lawlessness. Critical to this though, is the clearing of case backlogs in the Courts. This can be achieved by fast-tracking trials which present concern for public security, public interest, victims’ needs and vulnerability and special needs of accused persons. For example, public security concerns involve accused persons who are assessed to pose a threat to individuals or the public at large and are being granted bail routinely. Very often we hear of persons who are charged with multiple murders, armed robberies, sexual assault and gun crimes being granted bail. The administration of bail should take into consideration the concerns for public security and protection from violent offenders. Nevertheless, accused persons should not be held indefinitely for trial. Hence, a more conservative approach to the administration of bail should be matched to the urgency of the trial. The Courts should move quickly to exonerate innocent persons and swiftly convict and sentence those who are guilty so that the community can get a sense of assurance that it will not be threatened by the perpetrator of violent crimes.

Public interest imperative refers to cases that are of such critical or high-level public interest that their trial should be done expeditiously, and these apply especially to high-profile matters involving serious violence against vulnerable members of the population, rape matters, or the application of new legislation such as the Anti-gang Act in bringing down organized crime syndicates. These matters should be tried as a matter of priority to address or satisfy public interest and public concerns. In the case of new legislations such as the Anti-gang Act, the police should be given the opportunity to test their efficiency and competence in applying new laws to deal with our crime problem. Since the enactment of the Anti-gang law, 4 years ago, none of the cases made by the police under this law have yet been tried and the law is now up for review. How can the law be reviewed without first testing its effectiveness or the state of police investigative techniques under the new law?

The introduction of judicial specialization for financial crimes, complex frauds and trial of matters under the Anti-gang legislation requires specialist prosecutors who are capable of presenting evidence, much of which may involve witnesses whose identities cannot be disclosed or who may not be willing to appear in open court but instead opt to provide evidence from remote locations, such as in prisons. In instances of this nature the Plea Bargaining Legislation is applicable and attorneys assigned to these cases would have done extensive studies in organized crime, gangs, and the application of mutual legal assistance treaties. Additionally, they should be comfortable in working alongside the police in extending investigations aimed at bringing down crime syndicates, often involving very dangerous people such as drug lords, gun runners, extortionists, and persons involved in money laundering.

The introduction of mandatory minimum sentences for guns, serious narcotics offences, lottery scamming, extortion, rape and crimes committed pursuant to gang activities should be implemented. The most logical way to handle this matter is to ensure that the punishment matches the crime. In a society as small as ours, the government must be determined to match the high murder rate, use of illegal guns in criminal activities and the enforcement of a code of silence in communities with sentences that are commensurate with the crime. One way of accomplishing this is to punish people who acquire and use illegal guns so severely that others will be deterred or dissuaded from using guns to commit crimes. The proposal is for mandatory minimum sentence to be implemented and no discretion should be exercised for early release of persons who have committed these crimes.

Creating a culture of lawfulness cannot be done through goodwill but is achievable through a systematic approach which incorporates formalizing sentencing guidelines, utilizing the Plea Bargaining Law to encourage guilty pleas, exploiting the knowledge of convicted criminals in prosecuting others, dismantling criminal networks and clearing case backlogs in the judicial system.

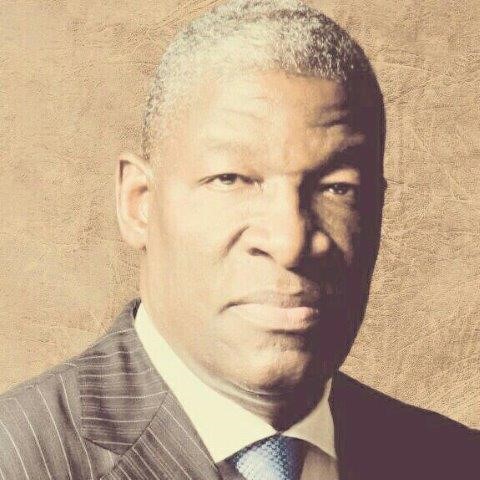

Author: Owen Ellington, C.D., J.P., MSc., BSc. Hons., Commissioner of Police (Retired)

Executive Director

Centre for Security Counter Terrorism and Non-Proliferation (CSCTN)

Caribbean Maritime University

Recent Comments